Federalism, Now More Than Ever

In crafting our constitutional arrangement, the Framers chose a political union that divides power between a central government and member sovereigns. Federalism, they believed, was the best way to ensure a harmonious union between separate states with distinct cultures and political preferences. Yet over the past century, our political system has become increasingly centralized, with the federal government prescribing one-size-fits-all policy in some of the most contested areas of public discourse, like healthcare, education, and entitlements. The consequences of this consolidation are palpable — our country is politically fractured, with diverse sectors of society straining under the weight of policy dictated by distant lawmakers unacquainted with the needs of their constituents. By returning power to the states — those same powers expressly reserved to them under the Tenth Amendment — we can hope for some semblance of harmony.

While the Constitution clearly envisions a federal system, American federalism is, in part, the result of historical happenstance. Our democratic republic took form from thirteen colonies that came together as thirteen independent states. But the Framers were intentional in their decision to preserve the arrangement, believing that government that is closer to the people it serves is more effective.

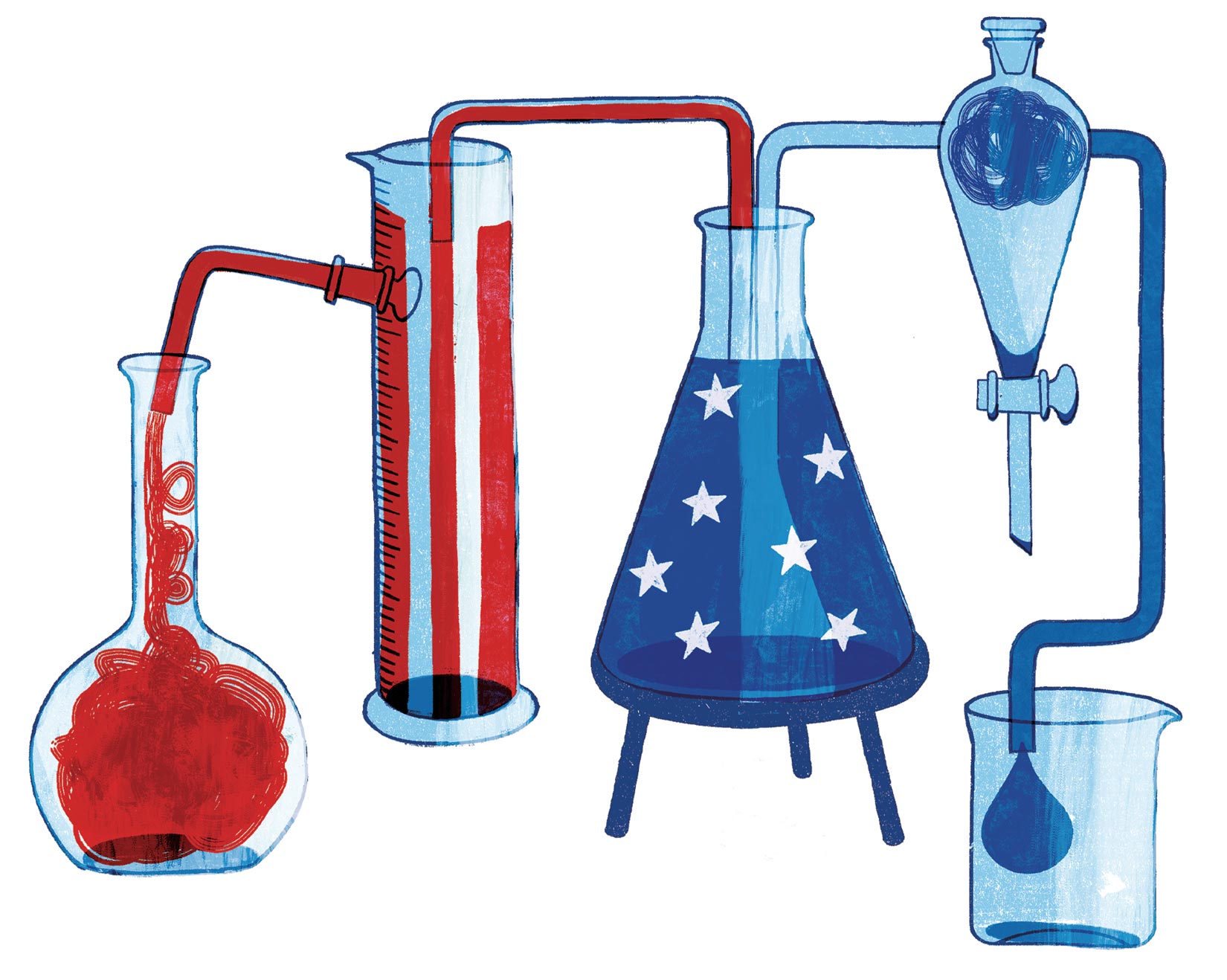

Even if the Constitution did not clearly prescribe federalism, however, there are practical reasons to embrace the federal model. Much like the principle of subsidiarity, federalism promotes the common good: By retaining political authority at more localized levels of civic society, individuals are more likely to participate directly in crafting solutions to their own problems, which allows human dignity to flourish. Federalism also incentivizes a race to the top, whereby states are in constant competition to provide better governance and better policy for their citizens. And by allowing states to operate as “laboratories of democracy,” all Americans benefit. When one state shows that a particular policy works well, other states will likely follow suit and attempt to replicate it. But if a particular policy fails, Americans in the other 49 states are spared from having to suffer under it.

Despite these practical — and constitutional — reasons for embracing federalism, our national government has ballooned in size and power over the last two decades. And no one party is to blame. While centralization has, in recent decades, been associated with the Democratic Party, both parties have shown themselves to be fair-weather friends of centralized government. Whenever the balance of power shifts at the national level, the party in power is happy to wield the mighty sword of federal authority, while the party in the minority parries with the shield of federalism. During the Clinton Administration, for example, federalism had a resurgence among conservatives. Variously dubbed “New Federalism” or the “Devolution Revolution,” the federalism of the 1990’s was closely associated with the conservative push for, among other things, reassigning the administration of social services to the states. During the Bush Administration, however, many of these same conservatives began to advocate for increased national control over education and healthcare. Most recently, during the Trump Administration, “blue states” became some of the strongest advocates of federalism, as they tried to resist federal policy in areas like immigration and the environment. California, for example, leaned heavily on principles of federalism and the related anti-commandeering doctrine to defend its “sanctuary state” from the Trump Administration’s influence.

But is this constant vacillation between federal and state control good for our country and our national discourse? Perhaps instead of expanding and contracting our view of states’ rights with each election cycle, we would be wise to consider embracing our federal system as it was originally understood, regardless of which way the political winds are blowing. Indeed, it has often worked well for us when we’ve done just that.

Most recently, the COVID-19 pandemic has become a paradigm for how essential and effective federalism is. Florida, for instance, has had success in reducing deaths and overall infections, even while being home to one of the highest percentages of high-risk individuals in the country. Other states, like New York, have been abject failures. Our federal system allowed states to innovate and tailor their response to the pandemic to the needs of their own people and their own circumstances. Had Washington dictated a one-size-fits all response, all states — and thus the entire country — would have risked more infections and more lives lost. Indeed, the state-level response to the COVID-19 pandemic has become a case in point for our federal system.

Perhaps the most compelling counterargument to a full-scale embrace of federalism is the fact that, at the time in American history when states had the most independence, many states endorsed the institution of slavery, culminating in the Civil War. How then can we say that ceding power back to the states is a prudent strategy for creating harmony in our nation? The answer lies in a proper understanding of the balance between state and federal authority. To be sure, the federal government has a crucial role to play in a healthy federal system. The federal government should take seriously its duty to enforce the Reconstruction amendments, which prevent states from legalizing slavery and violating the individual rights guaranteed by the Constitution. In fact, the absence of such national authority in the early years of the Republic allowed slavery to expand. But apart from the powers expressly granted to the federal government — crafting foreign policy, regulating interstate commerce, protecting those rights guaranteed under the Reconstruction amendments, and a handful of other powers — the Constitution contemplates strong state governments that are free to develop their own political systems. This is the vision of federalism to which we should return.

When our federal system was established in July of 1776, an estimated 2.5 million people lived in the thirteen colonies. Today, we have over 330 million — over 130 times the size at the Founding — and our population is more diverse than ever before. It should come as no surprise then that Americans have divergent views on every political and cultural issue imaginable. Conservatives might prefer to live in Arizona, with a strong school choice system and relaxed gun laws. Liberals might prefer Massachusetts, with a robust public school system and some of the most restrictive gun laws in the country. Rather than jamming a giant square peg in fifty round holes — and generating hostility and ineffective policy in the process — we should let these laboratories of democracy coexist, whether they fail or flourish. While this return to our roots is unlikely to solve all our political woes, restoring our federal system would be a strong first step in repairing our fractured nation.