Vietnam

Revisited

The pandemic forced an immediate all-hands-on-deck conversion from in-person learning to virtual education. The terrorist attacks in 2001 fostered crisis counseling and a sustained discussion about the rule of law and civil liberties. The 2008 recession tested the Law School’s model of preparing students to succeed beyond their first job in an ever-changing profession that proved susceptible to economic pressures.

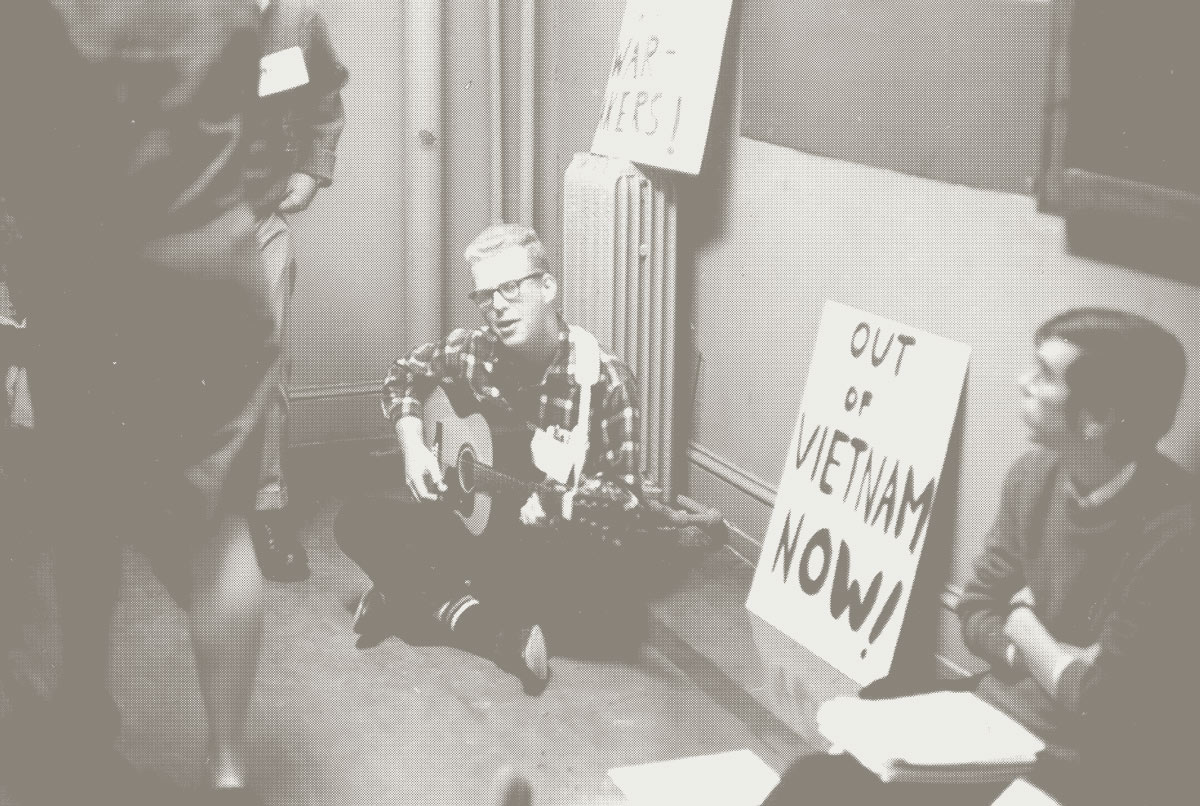

In this issue, we revisit the Vietnam era a half-century later. It was a time when students re-examined their values as the draft loomed over them and the country came apart. By Larry Teitelbaum

Vietnam

Revisited

The pandemic forced an immediate all-hands-on-deck conversion from in-person learning to virtual education. The terrorist attacks in 2001 fostered crisis counseling and a sustained discussion about the rule of law and civil liberties. The 2008 recession tested the Law School’s model of preparing students to succeed beyond their first job in an ever-changing profession that proved susceptible to economic pressures.

In this issue, we revisit the Vietnam era a half-century later. It was a time when students re-examined their values as the draft loomed over them and the country came apart. By Larry Teitelbaum

eter Marvin C’68, L’72 saw the writing on the wall when President Johnson eliminated the graduate school deferment. Indeed, Marvin received a notice from his draft board before he even completed his undergraduate studies at Penn informing him of his 1A status upon graduation. Until then, he had planned to enter Penn Law School in the Fall. Instead, he took what we would now call a gap year and joined the Army Reserve, committing himself to a six-year hitch. He would submit to six months of basic training, monthly meetings and two weeks of drills every summer. In his mind, a fair exchange if it kept him out of Vietnam.

He arrived on campus a year later as a “conscientious acceptor,” a term of art coined in The New York Times to describe reservists who made their peace with part-time military service. In a matter of months, the war and accompanying protests turned deadlier with the invasion of Cambodia and the killing by the National Guard of four Kent State students who were protesting the war on campus.

It all reached a boiling point with the approach of final exams in the Spring of 1970. Marvin remembers the conflicting emotions swirling at the Law School. The escalation and murders consumed the energies of many Penn Law students, to the point where they felt exams were an afterthought, especially with a huge protest planned in Washington around the same time.

“There was a significant feeling among a number of students that this was an important time to be demonstrating, to be lobbying our senators and representatives,” recalled Marvin, a longtime small firm and solo practitioner and former adjunct professor at the Law School who taught Common Law Contract for Civil Lawyers to LLM students. “There were more important things going on than taking law school exams.”

Students were given a choice to take the exams for grades on the scheduled date or defer them until the summer under a pass/fail system, an elegant solution that Marvin believes passed muster with most students, at least a third of whom left campus soon after to attend the Washington protest. It was a rare occurrence, repeated fifty years later, when Dean Ted Ruger and the faculty voted to make Spring 2020 exams credit/fail during the COVID pandemic.

While Fordham made accommodations for students, he offered no olive branch to leaders who plunged America into deepening involvement in the Vietnam War. Consider what happened on Law Alumni Day in 1970, a traditional event where one could hear pieties and paens to the law and to the Law School. Not on this day. In what amounted to a valedictory address, Fordham, a man of measured words and moral rectitude who would step down at the end of the school year after 18 years as Dean, used his platform to rail against the war, calling it a “cancer” and a “profound moral disaster,” according to an account in the Summer 1970 issue of what was then known as the Law Alumni Journal.

True to his decision to institute the option for pass/fail exams, Fordham said he empathized with students who were willing to risk their academic standing in honor of their principles, and so he felt justified giving them every opportunity to curtail their studies in favor of political activism.

“It was difficult for many of us to square this new area we were going into — the traditional idea of being a lawyer — with the chaos outside,” said Frenkel, who, like some of his classmates, wrestled with dropping out of law school.

“Why were we in law school? Why weren’t we on the streets? Why did we care about whether a contract was enforceable when the world was going to end?”

Normally, Frenkel would have gone directly from Wharton to law school. But these weren’t normal times. Frenkel and his classmates had weathered the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy in 1968 and watched with despair TV coverage of violent clashes between police and demonstrators at the Democratic convention in Chicago.

During his year off in the Army Reserve, Frenkel got in hot water with his military command by going public with his opposition to the war. He joined a group called Reservists Against the War and spoke out at a forum at Irvine Auditorium that was covered by the old Evening Bulletin newspaper.

He later learned of the brass’ displeasure when, on weekend leave from his summer duty for the wedding of a law school classmate, Russ Henkin L’72, his father’s car broke down and he couldn’t make it back to the base that night. Frenkel attended the wedding with another classmate and fellow reservist, John Myers W’68, L’72. Both were charged with being AWOL.

Complaining that the charge was unjust, Frenkel and Myers soon found themselves in front of a base lawyer, who said to Frenkel: “Oh, so you’re the peace freak AWOL reservists.” Affronted by the comment, Frenkel’s classmate called his professor, Martha Field, for whom he was a research assistant, and asked for her help. In a phone call, Field threatened to sue the commanders for violating the students’ First Amendment right to protest, according to Frenkel.

Looking back, what motivated Field, now the Langdell Professor of Law at Harvard Law School, to intervene? “The war was certainly in the back of my mind,” recalled Field, who taught a class on Military and Selective Service Law when she first arrived at Penn in 1969. “We all were concerned about the war and doing anything we could. I just don’t remember a lot of demonstrations against the war by my students. I don’t think they were burning draft cards or American flags; anyway they did not come to me for help on those things. But of course, when John and Doug were treated unjustly, I wanted to help them out in any way I could.”

Professor Paul Bender, a Constitutional Law scholar who now teaches at Arizona State University School of Law, sometimes found himself on the front lines. Bender collaborated with the ACLU, on whose board he served, or individually represented demonstrators who had been arrested.

His leanings were apparent in class. Openly opposed to the war, Bender said it was “impossible” to avoid the subject in a class centered on Constitutional issues. “You could hardly hide it,” he said.

nlike Marvin and Frenkel, John Clair L’72 failed in his attempt to join an Army Reserve or National Guard unit. No slots available. Three weeks into his 1L year, Clair was drafted. He asked the military if he could finish the school year. Permission granted.

At the end of the school year, he reported for what would be six months of basic and advanced training, and then off to Vietnam as a field artilleryman. He saw combat during his year of service.

“I wasn’t particularly enthusiastic about it at the time,” Clair said. But Clair, who retired several years ago from Latham & Watkins in Los Angeles, bore no bitterness. In fact, he said, his impending service motivated him to relish that year in law school, the Socratic Method being preferable to sparring with the Viet Cong.

Bob Heim W’64, L’72, a partner at Dechert LLP in Philadelphia, had an even longer interregnum. He shipped off to the Navy after graduating from Penn, serving four years as a naval officer on a destroyer and at a naval base.

While he was in high school, Heim aced a Naval aptitude test. The Navy offered him a four-year scholarship to any college or university in the country. He couldn’t turn that down given his father’s inability to finance his higher education.

When he returned to campus to start law school, Heim felt he had lost a step away from the intellectual ferment for so long. “My first impression (was) … God, these people all seem so much smarter than I am, (but) you got over that in a few weeks.”

He also felt mixed emotions about the war. Sequestered in the Navy, he listened mainly to Armed Forces Radio and didn’t grasp the growing anti-war sentiment in America. Even though he grew to see the war as “a mistake of colossal proportions,” in law school he chafed at times at what he perceived as “vociferous” criticism of the military, which made him want to defend his fellow veterans. “It was kind of confusing in some ways emotionally,” Heim said.

Nonetheless, neither Clair nor Heim suffered fallout among their classmates due to their military service. Heim was elected a class officer in his 1L year and as such helped negotiate the terms of the pass/fail exams with Dean Fordham.

Clair remembers some gung-ho veterans wearing their uniforms to class, but he kept a low profile, preferring to blend in. When he returned to the Law School for the Spring semester in 1970, he said he “wanted to put as much distance as I could between my experience (in Vietnam) and where I was going in the future.”

“I felt like the war was a mistake before I went, it was a mistake while I was there, it was a mistake when I got back,” Clair said.

or Holly Maguigan L’72, the Vietnam War was traumatic. As one of the relatively few women in her entering class, she did not have to worry about the draft. However, she found the war immoral and a waste of human life.

“The idea that people were being slaughtered just for American hegemony made no sense at all,” said Maguigan, echoing the sentiments of Dean Fordham. She attended a demonstration during her first week of law school. “Being anti-war seemed to me key and important. Something a person had to do. I would say it was a main event. There was law school and there was the war.”

Maguigan, Professor of Clinical Law Emerita at the New York University School of Law, went on to participate in many protests, all of which were peaceful, she noted. “We didn’t cause a ruckus,” Maguigan said, explaining that she never wanted to get arrested and test the Law School’s reaction.

For many students, the 2L and 3L years passed with less fanfare and commotion. Maybe they became inured to the war or encouraged by signs that it was slowly winding down as America gradually withdrew troops from Southeast Asia. Whatever it was, these were productive years for members of the Class of 1972.

Maguigan interned at the Defenders Office in Philadelphia, whose mission struck a chord with her.

Doug Frenkel spent parts of his 2L year as a psychiatry resident at Hahnemann Hospital and as a student-intern at the Law School’s Health Law Project under Professor Ed Sparer, and in his 3L year was an extern in the Community Law and Criminal Law Litigation program overseen by a young David Rudovsky, who went on to become a legendary member of the faculty.

Bob Heim, a little older than most of the class, had a wife and young child to support. He taught economics at night at Pierce Junior College. (He earned an MBA while in the Navy.)

In addition to his time as Associate Editor and Research Editor on the Law Review, Peter Marvin served as student representative on the faculty hiring committee and as a research assistant to Professor Paul Bender, who had become General Counsel of the National Commission on Obscenity and Pornography. Marvin helped him with that work.

The pass/fail exam debate became an historical footnote — but not for Holly Maguigan. Her opposition to grades was as fervent as her opposition to the war. She and a group of classmates lobbied hard for pass-fail. And at least for her it had nothing to do with the war. She refused to accept a grade in the following years as well because she didn’t want to be judged on that basis. Overall, she concedes that the pass-fail system worked out well, although she wishes it had become permanent.

Heims opted for grades, taking the exams on time; Marvin took some on time, one late and competed in the Law Review writing competition; Frenkel went his own way.

Frenkel spent the summer in Vermont working on a political campaign. Like a voter submitting an absentee ballot, he mailed in his exams.