Portrait of a Powerhouse

By Larry Teitelbaum

ven as an undergraduate at Penn, Roy Katzovicz C’95, L’98 had it all figured out. He’d be an academic, exercising his intellect to write erudite papers and lead lively discussions. Then he met Michael Wachter.

Wachter intuited that Katzovicz had unique talents better suited for business rather than professional endeavors. “You are what we call an entrepreneur,” said Katzovicz, recalling Wachter’s advice. He followed Wachter’s guidance and today Katzovicz is the CEO of Saddle Point Management, a multimillion-dollar investment firm in New York.

“Next to my parents, Michael Wachter had the single biggest influence in my life,” he said.

The Driving Force Behind the ILE

He also served as the University’s Deputy Provost and Interim Provost. On the 50th anniversary of his service to Penn, former President Judith Rodin CW’66, Hon ‘04, under whom he served, praised his strategic prowess, stellar intelligence, and keen wit.

However, Wachter is best known for being the guiding light of the Institute for Law & Economics (ILE) at the University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School. The ILE, a partnership among the Law School, Wharton, and Penn’s Department of Economics, was established in 1980 to provide economic analysis of legal issues. A turning point came in 1984, when then-Law School Dean Robert Mundheim appointed Wachter to lead the body to bring Wharton and the Law School together. The man for the job, Mundheim decided, was Michael Wachter, then a member of the Economics Department. Wachter agreed to move from Wharton to the Law School.

“Michael interacted well with his faculty colleagues at the Law School,” recalled Mundheim, Of Counsel in the Capital Markets practice at Shearman & Sterling LLP. “That’s what I hoped he would be able and willing to do – and he did. And that created an important relationship, and the ties between the Wharton School and the Law School deepened.”

Jill E. Fisch, Saul A. Fox Distinguished Professor of Business Law and Co-Director of the ILE, praised Wachter’s vision and leadership.

“Michael’s always been ahead of the curve,” said Fisch, “He was ahead of the curve in conceptualizing ILE. Michael also recognized that the focus of business law had changed in the world and adapted ILE to reflect those changes.”

“He reshaped how we think about issues surrounding corporate law with his singular vision and inspired and launched generations of students into fulfilling careers through his dedicated teaching and mentorship,” said Ted Ruger, Dean and Bernard G. Segal Professor of Law.

Michael A. Fitts, former Dean of the Law School and current President of Tulane University, said Wachter possessed “an innate ability to understand and create intellectual synergy. He instinctively knew the power of bringing different perspectives together in understanding and solving problems…fostering incredible insights into the inner workings of corporate law, solidifying ILE’s status as the preeminent corporate law center in the United States.”

Wachter transformed the ILE into a powerhouse institution that drew scholars, investment bankers, judges, and practitioners to the Law School for high-level policy discussions related to areas such as banking regulation, tax reform, collective bargaining, and shareholder activism.

The ILE benefited from its location between New York, the country’s economic center, and Delaware, where corporate law is adjudicated by the Delaware Supreme Court and the Delaware Court of Chancery, whose judges and justices participated in forums run by the ILE.

Under Wachter, the ILE became an important testing ground for innovative ideas as faculty from all over the country presented their papers for fervent academic debate. The ILE also became known for its learned seminars and roundtables and eventually branched out to sponsor prestigious lectures.

The Distinguished Jurist Lecture brought to campus Supreme Court Justices Anthony Kennedy and Antonin Scalia and Norman Veasey L’57, Chief Justice of the Delaware Supreme Court, while the Law and Entrepreneurship Lecture featured luminaries such as NBA Commissioner David Stern, Comcast President Brian Roberts, and Bristol-Myers Squibb Chairman and CEO Charles A. Heimbold L’60.

When Robert L. Friedman L’67 became Chair of the ILE Board in 2001, the institution was dominated by Pennsylvania participants. Wachter asked Friedman to leverage his investment community connections and recruit in New York.

“It truly became a go-to organization for lawyers in the corporate field, investment bankers and other financial executives,” said Friedman, retired Chief Legal Officer of The Blackstone Group. “It was all under Michael’s guise.”

Two New Yorkers who jumped aboard were Joe Frumkin L’85 and Charles “Casey” Cogut L’73.

Frumkin, Of Counsel at Sullivan & Cromwell LLP, said the ILE was a bracing experience for him.

“It was a much more academic perspective on current legal issues in corporate law than I was used to, and I found it incredibly invigorating and refreshing and useful. That’s what drew me into the ILE,” said Frumkin, who went on to serve as Co-Chair of the ILE Board of Advisors for 12 years.

“The existence and success of the ILE is almost entirely attributable to Michael’s vision and his effectiveness at executing his vision,” Frumkin continued. “Over time you came to understand that he was almost invariably right in what he wanted to do. His judgment was really extraordinary.”

Cogut, a retired partner at Simpson Thacher Bartlett LLP, served as Co-Chair of the ILE for a decade.

Cogut found his interaction with the Delaware judiciary through the ILE a rare, enlightening opportunity, especially because corporate lawyers generally do not interact with judges or have the chance to glean their insights into relevant issues facing practitioners.

Cogut credited Wachter for making this happen, and for his overall leadership and scholarship. “He was brilliant. (He was on) an intellectual plane at an altitude that I couldn’t come close to.”

The Life-Changing Teacher

Katzovicz quickly came under the tutelage of Wachter, ultimately spending seven years working for him, first as an administrative coordinator at ILE, where he collected, copied, and distributed academic papers to other professors on campus.

As he read the papers, Katzovicz became conversant enough in the subject matter to assist professors at the Law School, Wharton, and the Department of Economics with their research. This experience led him to coordinate corporate roundtables, where he met the country’s leading judges, high-profile investors, and highly successful corporate lawyers.

By the time Katzovicz finished law school, he had built a solid network bolstered by his extensive ILE experience. After graduation, Katzovicz joined Wachtell Lipton in New York, then clerked for the Honorable William Chandler of the Delaware Court of Chancery. He worked for Pershing Square Capital Management before starting Saddlepoint in 2018.

Wachter and his wife Susan met at Harvard, married in 1968, and collaborated on research and writing for the rest of their life together.

Wachter and his wife Susan met at Harvard, married in 1968, and collaborated on research and writing for the rest of their life together.Portraits in Time

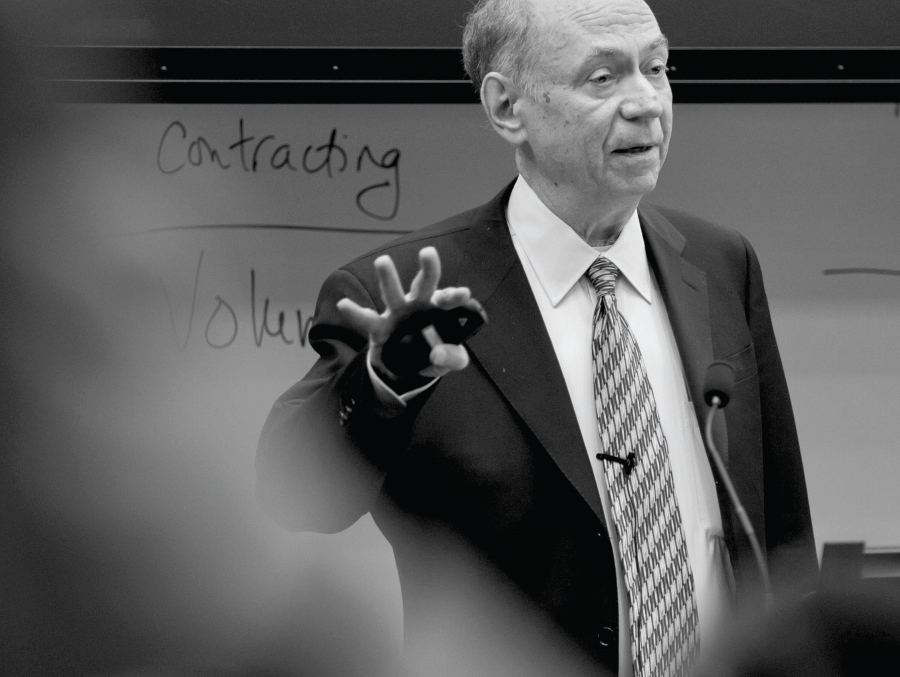

Michael Wachter taught a legendary course on Corporate Law, mentoring and inspiring a generation of students.

Michael Wachter taught a legendary course on Corporate Law, mentoring and inspiring a generation of students.Wachter also had a major impact on the life of Eric Klinger-Wilensky L’03.

“I was a very young, very green second-year law student from New York when I took his corporations class—a survey class—in old Room 100. He just asked if anybody would be interested in clerking in Delaware, to please come see him. I did, and he said thanks, and just that I’d better be prepared for class the next day, and I was.”

The Honorable E. Norman Veasey L’57, who was Chief Justice of the Delaware Supreme Court at that time, co-lectured the next day. “He went Socratic, and I guess I passed my test. … I never, ever thought about Delaware before. I got invited for an interview for a clerkship in the Court of Chancery, and I ended up having my career down here.”

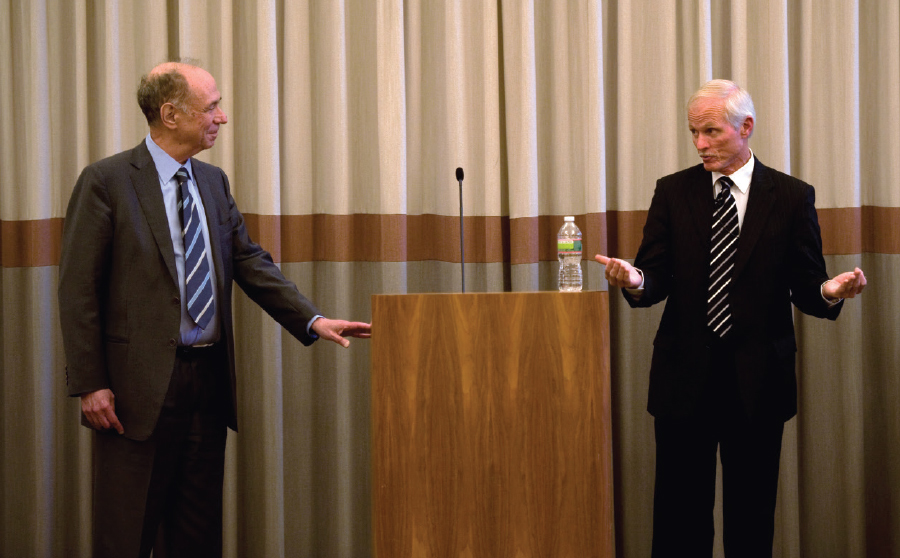

Wachter (left) leading discussion after William B. Chandler, former Chancellor on the Delaware Court of Chancery, delivered the Institute for Law and Economics’ Distinguished Jurist Lecture.

Wachter (left) leading discussion after William B. Chandler, former Chancellor on the Delaware Court of Chancery, delivered the Institute for Law and Economics’ Distinguished Jurist Lecture.“I kind of joke that absent Michael Wachter, I wouldn’t have been a clerk, I wouldn’t have met my now-husband, I wouldn’t have started my career here, I wouldn’t have had my kids.”

“[He] changed my life,” Klinger-Wilensky said. “Without a Michael Wachter, there’s no partnership at Morris Nichols, I would’ve just gone back up to New York. I found a real interest in Delaware corporate law because of him, and I pursued it. He gave me that interest.”

Since Wachter weaved the Delaware judiciary into the fabric of the ILE, it is only fitting that one of his former students became Vice Chancellor of the Delaware Court of Chancery.

The Honorable Lori Will L’09 also clerked for then-Vice Chancellor Strine after taking a seminar taught by Strine and Wachter.

“I owe a debt of gratitude to Professor Wachter for helping me to not be intimidated by that area of the law,” Will said. “There were no stupid questions. He would explain things in a way that was understandable for students coming at this for the first time.”

“He was such a legend,” she said. “I’ve always felt lucky I was able to take a class with him.”

The Pathbreaking Scholar

Wachter’s wife Susan, the Albert Sussman Professor of Real Estate, Professor of Finance, and Co-Director of the Penn Institute for Urban Research, summarized the salience of her husband’s work in a self-penned obituary.

She explained why it resonated and influenced the courts, his peers, and the field of law and economics.

Saul A. Fox Distinguished Professor of Business Law and Co-Director of the Institute for Law & Economics

She said her husband’s early work also examined the persistent puzzle of why different industries command such different wages, even though they required similar levels of skill, and even after controlling productivity.

The dominant view of the time, she wrote, assigned these differentials to lack of competitive forces—some industries simply had a higher ability to pay. Wachter showed that wage differentials depended on unemployment; that low-wage industries were able to reduce their relative wages in periods of high unemployment. With its mix of competitive and Keynesian reasoning, Susan Wachter explained, the paper changed the way the field thought about unemployment and wage fluctuations. This work also helped give rise to the concept of the natural rate of unemployment which is still in use today.

Ed Rock L’83, former Co-Director of the Institute for Law and Economics and current Martin Lipton Professor of Law and Co-Director of the Institute for Corporate Governance & Finance at NYU School of Law, marveled at Wachter’s originality.

Rock, who co-wrote numerous papers with Wachter, said “he had this way of thinking that could be opaque to me. But when you finally understood his point, it was almost always right.”

“Michael was a first-rate economist and had very deep, very good economic intuitions. And he brought those to labor law and corporate law scholarship,” Rock said. “His economic understanding gave him a leg up in his writing.”

Rock said Wachter’s work was not only perceptive but influential, pointing to a paper Wachter co-wrote with ILE Executive Director Larry Hamermesh titled “The Short and Puzzling Life of the Implicit Minority Discount,” which won a Top Ten award in 2008 as one of the best corporate and securities articles of the year. Wachter also won Top Ten awards in 2009, 2010, 2012, 2013, and 2015.

As Hamermesh explained, Delaware courts traditionally said that the fair value of a share of stock is its proportionate share of the fair value of the company overall. The question then became how is fair value measured? One way, Hamermesh went on, is to rely on the market price of the stock on the New York Stock Exchange.

But Delaware courts began to think that looking only at the market value of stock understated the value of the company because that only showed minority interests—“companies with millions and billions of shares, even if you sell more than 10,000, it’s still a drop in the bucket.” Courts began to think that these smaller stock trades, because they involved minority interests, reflected a discount relative to the fair value of a company—thus the phrase “implicit minority discount.”

“And then, this was mostly Wachter, he says, ‘wait a minute, there’s no such thing as a minority discount, because in fact stock prices are on average a pretty good indicator of what a company overall is worth— because the stock market is measuring and reflecting the present value of how much this company is going to earn over time.’ ”

“It doesn’t discount because of a minority position, and it’s just what you get when companies sell stocks to the public, that’s the basis on which they trade, so it’s perfectly ordinarily reasonable to use market price,” Hamermesh summed up.

He said before the articles were published, financial experts would “come up with these wildly disparate estimates of fair value.”

“Our articles got cited a lot in part of the discussion. They certainly . . . may have influenced the trend in Delaware courts to rely on actual market transactions to determine fair value.”

Over the course of 50 years, Wachter forged careers, ran institutions, and educated his colleagues, all the while displaying an exacting intellect—as Rock quickly came to learn.

When Wachter completed his tenure in the provost’s office, he decided to stretch his academic muscles and switch his focus from labor economics to corporate law.

With characteristic rigor, Wachter attended Rock’s introductory “Corporations” class two years in a row. He took detailed notes and asked hard questions, keeping Rock on his toes.

“I never taught so well as those two years,” Rock said, laughing at the memory.